AI Advances in Seal Research: Turning Challenges into Opportunities – Guest Blog

Learn how Claire Stainfield is utilising advances in AI to support seal research. When used thoughtfully, AI can be a powerful tool.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) seems to make headlines daily—often with alarming phrases about “robots taking over” or “AI replacing jobs”. But for those of us in the field of conservation, the story looks quite different. Used thoughtfully, AI can be a powerful tool that streamlines complex tasks, saving valuable time and helping us achieve what once felt impossible.

When I began my PhD, I never imagined I’d end up delving into the world of AI models. My focus was on surveying the seal colony at Newburgh Seal Beach, using drones to capture aerial photographs. From above, it’s easy to see why drones have become such valuable tools. The accuracy and scale of data they provide far surpass the traditional binocular counts we once relied on. But as I quickly discovered, the challenge wasn’t in collecting the images—it was in processing them.

Each survey produced hundreds of photos and, on average, over 1,000 seals per session. Manually counting seals across these images was not only time-consuming but also unsustainable for long-term monitoring. I soon realised that while technology made data collection easier, it hadn’t yet solved the issue of data processing—the real bottleneck for many reserves and research teams.

Turning Challenges into Opportunities

Determined to find a practical solution, I connected with colleagues at the University of Gothenburg, who were already experimenting with AI models for aerial wildlife surveys. Their methods were impressive but required advanced coding knowledge and expensive software subscriptions — luxuries that conservation budgets rarely allow.

The breakthrough came unexpectedly at a workshop at the University of Glasgow, where I was introduced to a piece of open-source software called RootPainter. Originally designed to track root growth, RootPainter uses a simple yet effective interface: with a graphics pen, you literally “colour in” examples to teach the model what to recognise. A lecturer had already adapted it to identify marine sponges, and I wondered—could it work for seals?

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Before going further, it’s worth explaining a small but important distinction. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the broad term for any computer system that performs tasks requiring human-like intelligence — things like recognising images or making decisions. Machine Learning (ML) is one specific method within AI where the computer learns from data rather than being programmed step-by-step. So, in this project, when the software learns what a seal looks like by analysing hundreds of training images, that’s machine learning — one branch of the wider world of AI.

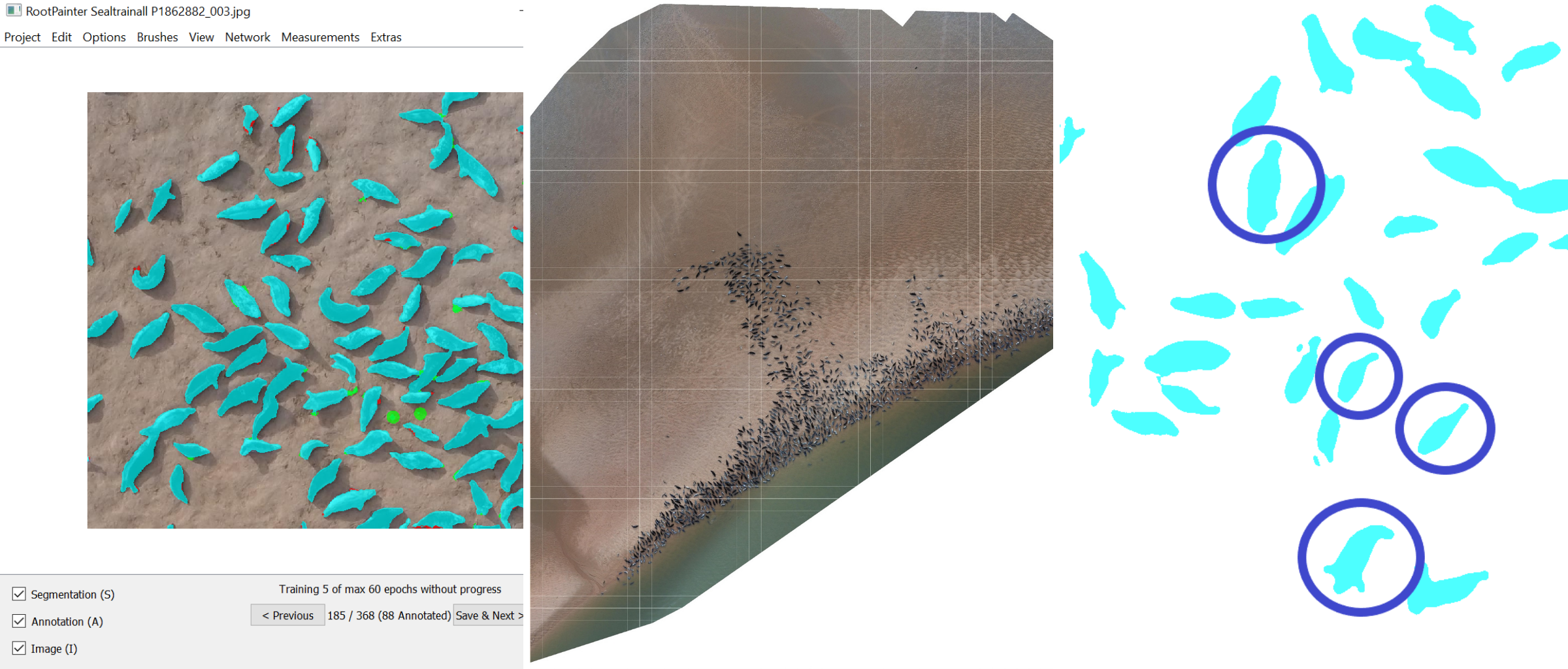

Image showing Rootpainter screen showing the annotations when training the AI, a full haul-out orthomosaic and a close-up screengrab of a perfect example of the model working well.

Using RootPainter

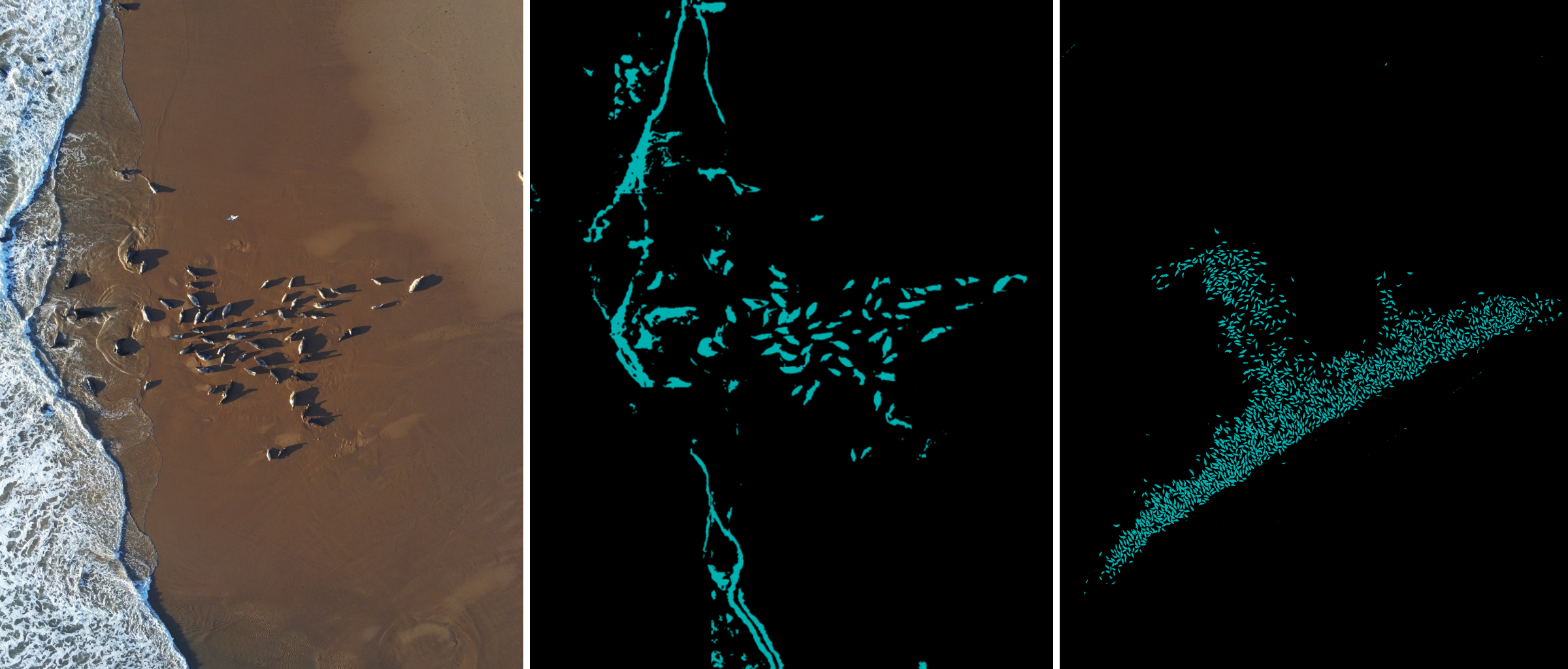

After a year of training the model using hundreds of drone images, the answer is a resounding yes. It hasn’t been without challenges—teaching the AI to distinguish between dark seals and shadowy rocks, or between waves and flippers, has tested my patience more than once. But the results are remarkable. What once took several hours to process manually can now be done in under a minute. Under ideal lighting — overcast skies and calm seas — the model’s counts are within 10% accuracy of a human observer.

Of course, it’s important to recognise that AI doesn’t come without environmental costs. Training large models can be energy-intensive, contributing to significant carbon emissions if run on high-powered servers. The positive news is that tools like RootPainter are much lighter — they can run on standard computers rather than energy-hungry data centres. For conservation researchers, that’s a crucial distinction: it means we can harness the benefits of AI without adding heavily to the environmental burden we’re trying to protect against.

The best part? The software is completely free and adaptable. That means other researchers, conservationists, and reserves — no matter their technical background — can use and retrain the model for their own sites and species.

Image showing the original image inputted to AI, the early stages of the AI, and the accurate output that helps with seal research

AI Advances in Seal Research

This project has shown me that AI doesn’t need to be intimidating or out of reach. When applied thoughtfully, it can make conservation work more efficient, inclusive, and sustainable. As we continue developing and refining the model, I’m always looking for collaborators — whether you have seal imagery to contribute, experience in AI, or just curiosity about what’s next.

Because when conservation meets innovation, even the most unfeasible tasks can start to feel achievable.

Seals in the Ythan Estuary

If you’ve been following this project, Claire is still accepting GPS tracks from volunteers to support another chapter of her PhD research. To contribute your data or find out more, please get in touch at GPS@sruc.ac.uk or visit the Aberdeen Marine Mammal Project website for details.

View from the drone perspective with lots of seals - takes lots of time to count!

More News

Claire Stainfield

SRUC PhD Candidate